I felt uncomfortable watching Crumb. I felt uncomfortable as I looked for a picture of Crumb to include in this review (his comic depicting the rape of a headless woman was ubiquitous irrespective of how I phrased my search query). Everything about Robert Crumb makes me uncomfortable. As an eccentric and a creative, I identify with him. As a female, I find him kind of frightening. On a more general note, I was disturbed by seeing the unique misery of a nightmarish childhood so well articulated in this documentary. It really made me feel something, and although those feelings were mostly negative (i.e. horror, disturbance, fear) this film really is a remarkable achievement.

So much of what was documented by Zwigoff in Crumb could not have been fabricated for the purposes of directing a fictional movie. Or at least if it were, I don’t know that I could have retained my willing suspension of disbelief. I went into the film expecting to learn about Robert Crumb’s creative process. Instead, I found myself gripped by a psychological deep-dive into a highly dysfunctional family.

There was so much honesty in this film – honesty about some of the greatest miseries of the human experience. And yet, much of it was related with a laugh or a chuckle. There were a number of scenes that I had to re-watch, given the easy manner in which travesties were related.

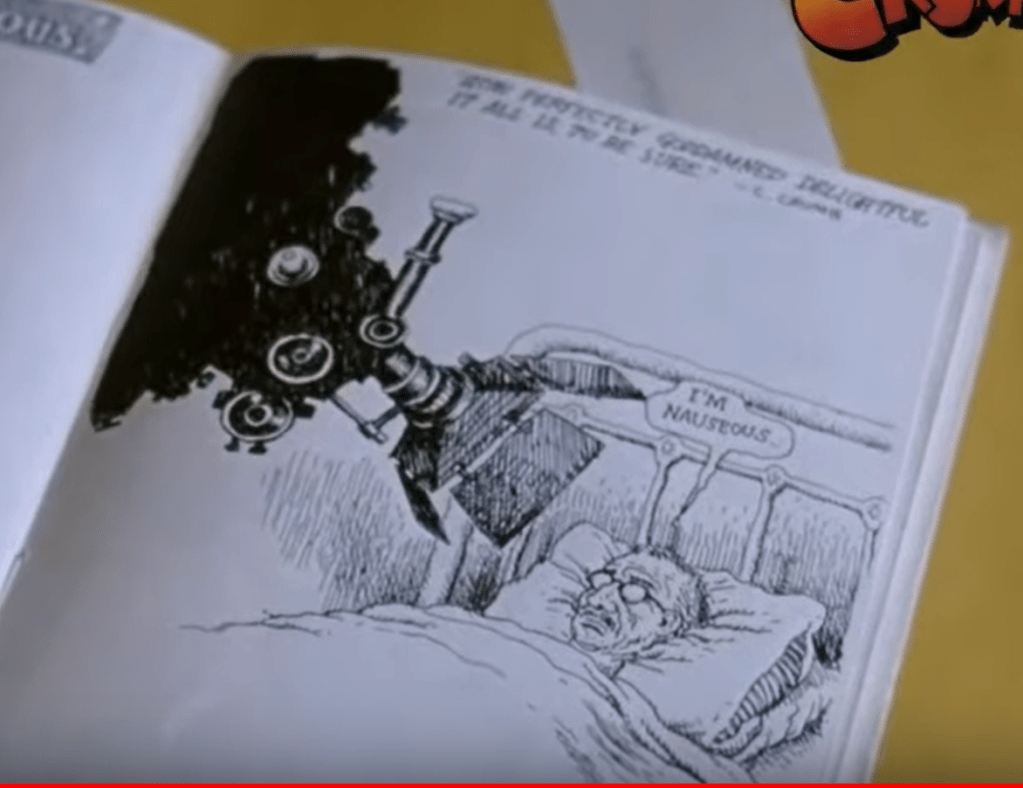

I was amused when Robert Crumb presented his comic depicting how he felt during the filming process. The caption “How perfectly goddamned delightful it all is, to be sure” is a catch-phrase coined by Robert’s brother, Charles Crumb. This could be said to capture the Crumb family attitude – ironic acceptance of one’s situation, given the futility of resistance.

I mentioned that I find Robert Crumb frightening because I am a female. There is a unique type of disturbance one feels at being simultaneously an object of hatred and lust. Crumb is forthcoming about what he terms his “hostility towards women”. There is a remarkable scene in the documentary where his former partner is discussing the breakdown of their relationship. In response, Crumb laughingly says “do you think I’m sadistic?” and grabs her roughly by the face. I was at once shocked and intrigued. I am still reeling that, of the Crumb family, Robert Crumb is the most well-adjusted.

Despite the discomfort some of us feel about Crumb’s depiction of violence and sexual deviance in his artwork, the fact that it evokes such a strong response suggests that it communicates an evocative, perhaps universal, message. Indeed, in portraying his most depraved and outrageous ideas and thoughts, Crumb is doing what all great artists must do – expressing his true nature.

I see Crumb as a meditation on what circumstances give rise to the creative impulse. The art that the brothers – Maxon, Charles and Robert – produced felt necessary and driven, not the product of a fun pastime. It is often said that art is life-giving, but this film would never let its audience be so idealistic as to believe that. As Robert Crumb says “I start feeling depressed and suicidal if I don’t get to draw. But sometimes when I’m drawing, I feel suicidal too”.