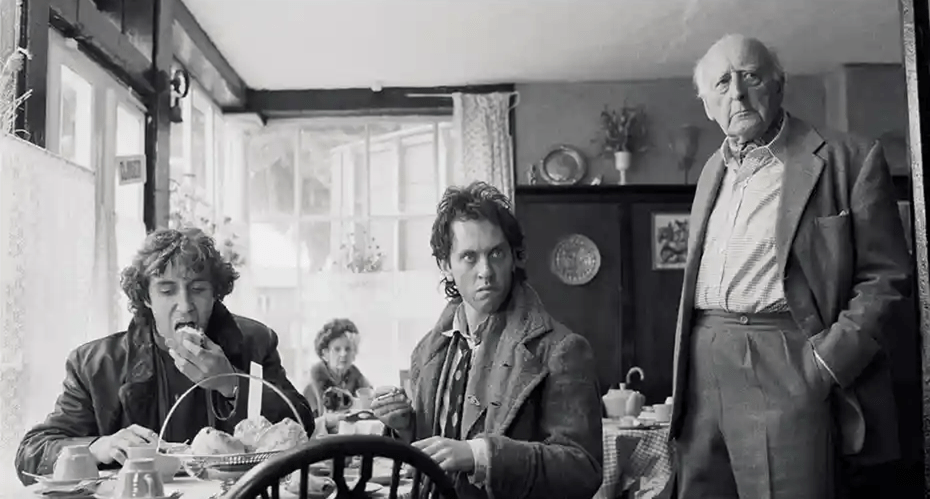

Withnail and I is a comedic horror about the recognition of one’s own depravity and its consequences. The narrative centres upon Withnail and Marwood (the titular ‘I’), a pair of impoverished creatives astounded by the indignity of their own circumstances, though doing nothing to improve upon them. Indeed, they live in a less dignified manner than their penury dictates due to their prolific substance-use and indolence. The audience is introduced to their shared London apartment through the abhorring, red-rimmed eyes of Marwood, where they are overwhelmed by a filth that has attained its own organic autonomy. Aware that they are ‘[…] drifting into the arena of the unwell [and] making an enemy of [their] own future’, the pair endeavour on a trip to the country in search of rejuvenation; however, the grotesquery proves inescapable and they are instead subject to a litany of vulgar events against a landscape rich in awfulness.

While the plot of Withnail lends itself to a typical narrative of drunken exploits, it transcends stereotype due to the curious poeticism of the derelicts it portrays. Their command of language and intertextual references denote an educated, Byronic, sensibility that renders the characters’ ruin more deeply felt by its stark juxtaposition. This is evident in Withnail’s recitation of the soliloquy What a Piece of Work is Man at the film’s conclusion:

‘I have of late, but wherefore I know not, lost all my mirth and indeed it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame the earth seems to me a sterile promontory’

This soliloquy – excerpted from Hamlet – expresses a loss of wonderment and inability to derive pleasure or interest from the world. Similarly, Marwood appraises the lowliness of their situation at the film’s commencement, whereupon the audience finds him nauseated by the gruesome humanity of a greasy spoon cafe, and prurient articles in the newspaper. His voiceover speaks to his disgust:

‘Thirteen million Londoners have to cope with this, and bake beans and allbran and rape, and I’m sitting in this bloody shack and I can’t cope with Withnail’.

Withnail and Marwood’s intellect affords them an uncomfortable level of insight into their lowly circumstances and speaks to the discomfiture of human consciousness. Had the protagonists been mere fools, they would lack the capacity to appreciate the full extent of their ruination; instead, they are afforded a dimensionality that lends the film a sense of latent tragedy.

The film’s sensibility is transformed from tragic to tragicomic by Withnail’s entitlement, which renders the indignities he suffers particularly potent. When subjugated to the cold of the London apartment, he complains:

‘I’m a trained actor reduced to the status of a bum. I mean look at us! Nothing that reasonable members of society demand as their rights!’

Withnail’s fury and pain in response to perceived injustices is often expressed in hyperbolic outbursts such as this. These outbursts are heightened – and have greater comedic effect – when he is slighted by those he considers beneath him. For example, he refuses an acting role, stating:

‘Bastard asked me to understudy Constantine in The Seagull. I’m not going to understudy anyone, especially that little pimp!’

Ironically, Withnail makes this proclamation whilst standing completely destitute in a telephone box, using funds gleaned from Marwood to make his calls. In terms of material circumstances, Withnail is no better than those he regards as plebians; however, his conceit is never mediated by his own relative destitution. Thus, Withnail is tormented by circumstance due to his immense pride and expectations of what is owed to him.

Marwood is similarly astounded by the realities of the world around him, though on account of his naivete rather than entitlement. He is surprised when his attempt to purchase eggs from a farmer’s wife is met with hostility, reflecting this was:

‘not the attitude I’d been given to expect from the H E Bates novel I’d read. I thought they’d all be out the back drinking cider, discussing butter’.

Further, when faced with the ordeal of butchering a live chicken, he suggests that Withnail ‘kill it instantly in case it starts trying to make friends with us’, indicating a storybook understanding of reality. This particular brand of naivete, premised on expectations based in literature, is characteristic of creative romanticism. The film repeatedly upsets this romantic sensibility, and Marwood’s resultant horror lends to the comedic thrust of Withnail and I.

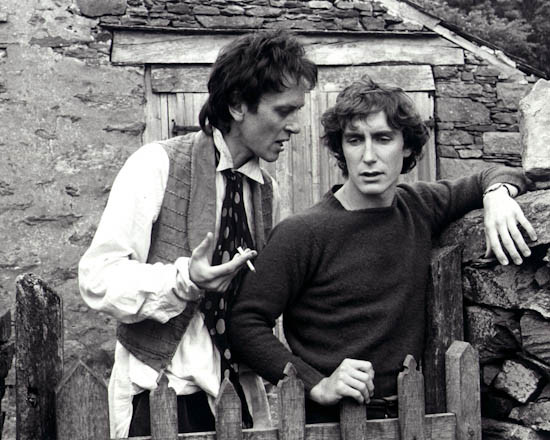

Withnail and I sits within the buddy-film genre, concerning itself with the intensity of companionship founded in shared destitution; however, the relationship it centres upon is more caustic than is typical of this oeuvre. While films such as Midnight Cowboy illustrate how the ecology of interdependence fostered by shared adversity is something of beauty, Withnail and I explores how a dysfunctional friendship can enable destructive behaviour and create a self-perpetuating stagnancy that impairs the growth of both parties involved. In Midnight Cowboy, the cold of their dilapidated apartment encourages Joe Buck and Ratso to dance together in a touching scene. The same circumstances in Withnail and I give rise to Withnail lathering himself in an entire tube of deep heat and advising Marwood ‘there’s nothing left for you’. From the beginning of the film, Withnail is presented as an affliction upon Marwood’s wellbeing, thereby driving the narrative toward a conclusion in which he transcends the negativity of Withnail’s orbit.

There is an interpretive project among a subset of viewers which contends that Withnail is enamoured with Marwood, albeit unrequitedly. Such viewers point to Withnail’s recitation of What a Piece of Work is Man at the film’s conclusion as indicative of his disinterest in women due to his repetition of the line ‘nor women neither’. Another favoured interpretive fragment is the lack of female presence in the film, save for the schoolgirls that Withnail venomously labels ‘scrubbers’. The sparsity of this evidence suggests that such interpretations are projecting homoerotocism onto the text (an act of Ho Yay[1]), rather than identifying any intentional coding of homoerotic ephemera into a cohesive subtext.

Nonetheless, predatory homoeroticism is an enduring theme in Withnail and I. This is embodied by Withnail’s lustful Uncle Monty, who attempts to impose himself upon Marwood during an overnight stay in his country cottage. When Monty’s advances are rejected, the action rises to a crescendo of visceral terror when he demands:

‘I mean to have you, even if it must be burglary!’

Marwood is a vessel for depicting male fear of homosexuality in Withnail and I. His immense anxiety is evident when he finds ‘I fuck arses’ inscribed on the wall of a pub bathroom, whereupon his voiceover and diegetic speech intermingle in an anticipatory prolepsis as he wonders whether someone has ‘written this in a moment of drunken sincerity’, and he is in imminent danger of rape. The portrayal of homosexuality in Withnail and I, particularly the anxiety surrounding it, serves to comment on male insecurity in a manner similar to texts such as American Psycho and Fight Club.

Withnail and I is delightfully caustic. It achieves great comic effect by upsetting both the genre conventions of the buddy-film, and the expectations of its protagonists, who consequently endure a near constant state of exasperation and distress throughout the film. Irrespective of Withnail and I’s comedic leanings, it is able to affect real tragedy by affording its protagonists an awareness of their unfortunate circumstances. This is powerfully felt at the film’s conclusion, where Withnail’s despairing recognition of his newfound solitude is masterfully depicted through the words Shakespeare afforded to his greatest tragic hero:

‘this majestical roof fretted with golden fire; why, it appeareth nothing to me but a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours. What a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, how like an angel in apprehension, how like a god! The beauty of the world, paragon of animals; and yet to me, what is this quintessence of dusk. Man delights not me, no, nor women neither’

In spite of this capacity for beauty and excellence, there is no redemption for Withnail. The wolves are his only audience, and – as is stated in the screenplay – even they are unimpressed.